- Home

- Maggie Rainey-Smith

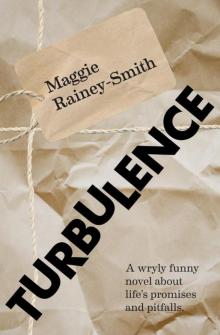

Turbulence

Turbulence Read online

Adam is fortyish, coasting along and relatively content while his glamorous partner, Louise, takes centre stage. But half a lifetime ago his aspirations were higher, and he was certain about the future he’d share with Judy.

When an unexpected invitation arrives, uncomfortable truths resurface and the secrets of the past spill out. How will Adam manage attending a reunion in the company of both Louise and Judy – not to mention stepfatherhood and a state of siege at work?

Punctuated by a sense of loss, Turbulence is a wryly funny look at life’s promises and pitfalls.

Praise for Maggie Rainey-Smith’s debut novel, About Turns:

‘Fun, but with a satisfying emotional depth’ – New Zealand Books

‘She has such a perfect pitch for the tragicomic incidents of everyday life’ – Sunday Star-Times

‘A very funny book, with some fabulous one-liners’ – Otago Daily Times

TURBULENCE

Maggie Rainey-Smith

For John

People I need to thank:

My family for their love and support, Shelley Dixon (first reader) for her helpful suggestions, Harriet Allan for her support and encouragement, Claire Gummer for her careful editing, and Allan Brown for advice on manufacturing. And to all my bookclub friends — thank you for believing in my dream.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter One

A tourist flight over the Milford Sound has been diverted due to turbulence.

The news reporter cleared his throat, coughed. ‘Excuse me,’ he said.

Adam turned the radio up.

A passenger on board the charter flight vomited as a result of the turbulence and his jaw locked open. The tourist has been flown to a nearby hospital so that his jaw can be unlocked.

Now the news reporter had a hint of humour in his voice and Adam thought about the poor sod with his jaw locked open, thought for a moment about the vomit and where it might have landed, changed down a gear at the give-way sign and joined the traffic at the roundabout — newly planted with fashionable grasses in various shades of brown.

Adam opened his own mouth wide, felt his jaw stretch and then gulped as he almost collided with a blue Leyland P76 — God, he hadn’t seen one of those since the seventies. Most of them had been recalled. A Leyland P76 in good nick too … still going … outdated and faulty from the start but there it was, an original.

The woman in the Leyland had looked curiously at him, slouched over the steering wheel, staring at her, his mouth wide open. Not ordinary wide open; the sort of wide open that could cause a car to crash.

Adam shut his mouth. His jaw felt bruised at the back near his troublesome molars. His mouth felt tender, cracked at the edges, over-stretched. The blue Leyland was in front of him now, having edged up on the inside of the roundabout and sped up.

The woman in the Leyland had a shaved head and three children free-flow (Tegel chicken style) in the back of the car. His first instinct was to censure her for being so careless. The way she sat — not back in the seat and not forward clutching the wheel like most women, instead jaunty and unconcerned, her children scattered in the back but somehow not abandoned — just unbuckled.

The woman was beside him now; they were moving together towards a merging lane. Momentarily, Adam was distracted by a small freckled face at the window of the Leyland, nose pressed up against the glass — and then he was angry … stupid bitch, he thought. Didn’t she know about seat belts? And before he knew it, the Leyland had moved ahead again, he was braking to avoid colliding and the freckled child was in the back window waving. Adam waved back but he wasn’t waving to the face in the Leyland — he was waving to another small face from another time … a face that was never going to leave; no matter how many times he waved goodbye.

Diving had been the only escape in the aftermath. He’d spent hours off Red Rocks and Makara, taking risks, flaunting his vulnerability in the depths, not wanting to die but not caring much about life. And then the water returned him to caring. The spectacle of life under water — barely noticed by the average person, but so intricate and so huge that his own small world mattered less and yet more. Salt water was for flesh wounds and his were deeper … even so, diving had soothed his wounds, if not healed them.

Adam used to believe that tragedies happened to other people. They were arbitrary, accidental, something you heard about second-hand. You thought how awful and wondered how the world could conspire to create such an event, so suddenly, out of nowhere. But he knew now this wasn’t what happened. The aftermath gave time to trace the peculiar line that led to the particular moment: particular to those involved and peculiar to those who were not.

The Leyland in front of him was belching grey clouds from a rusty exhaust. Adam switched the air-con from recycle to fresh and coughed as he inhaled the emissions. He liked the smell of burnt petrol. It conjured up his youth, the accompanying smell of lawn clippings in summer.

Now there were two freckled noses pressed against the back window. The driver had her head at an angle, as if she was looking both forward and back at the same time, as only a woman could. Multi-tasking. Except he noticed she had slowed down as she multi-tasked, and he had to adjust his own speed to compensate.

The woman in the Leyland reminded him of when he and Judy were first married. Her head (her jaunty head) evoked a time when to be jaunty was to be joyful.

Him and Judy, newly married, newly everything. How could he have been so damned innocent? So certain. He changed gear, checked his rear vision and grabbed the one small opportunity: a momentary gap in the commuter traffic and he was off, leaving behind the exhaust-belching almost-classic pale-blue Leyland.

Bugger, he’d forgotten Frankie. He pulled off The Esplanade into a side street and took a detour behind the glue factory, completing a sort of circle. Being there for Frankie was a part of his life that he understood. She was learning to dive and he’d encouraged her, promised to support her. Reliability was important — more important than love somehow. Love was unreliable. He couldn’t replace her real dad, but he wouldn’t let her down.

Adam often analysed love. He’d decided it worked best without too much analysis and with a lot of commitment. If he analysed his love for Louise it came up trumps on commitment — his. Freedom, she often reminded him, was the only true path to commitment.

A conscious choice, each day, to be together.

He was grateful. One failed marriage was more than enough for any man. Not expecting success was a sure way to avoid failure.

Once, Adam had tried to grapple with versions of love. He’d told Judy that he still loved her but was in love with Louise. This concept, before he’d given voice to it, had seemed like a fair summary. But as it moved to the spoken word, it sounded lame and self-serving. Defending Louise was his next step. A definite no-

no. Someone should have warned him about that! He’d earned Judy’s contempt for it, though he had to admit that her response had made it easier.

‘Cunt-struck!’

Love reduced to this. His feelings for Louise, construed as something so crude.

He’d never heard Judy speak like that, not that language, not that tone, not ever. But until then, he’d never stood before her, declaring his love for someone else.

She spat the words; not screaming, but cold and hard. Then she picked up his mobile phone (almost new and recently updated to access production stats from his work computer) and hurled it across the kitchen floor. He watched it explode into pieces with the SIM card disappearing under the fridge — and with that, Judy’s anger subsided. She became calm, rational, and composed … he saw the wound he had inflicted.

He often reran the scene. Judy reaching out to him saying she understood … his rebuttal (her anger was preferable) … Michael with cuddly-rug in tow, disturbed, thumb in his mouth, finger on his nose, watching from the doorway.

Over and over on replay: wanting to get down and find his SIM card (this still filled him with disgust) … Judy’s sudden reversal from anger to composure (he was an onlooker, an observer, emotionally disconnected) … Michael in the doorway, still sleepy, startled … the moment that changed their lives, the moment he could have changed.

Frankie at the car window, changed from her wetsuit to track pants, hair swept up in a topknot with a pink elastic tie, innocence mouthing McDonald’s at him through the glass. He would suffer indigestion but watching Frankie devour a cheeseburger, chips and a thickshake was worth it. She took dainty bites of bun and moved recalcitrant wisps of hair from her face, crammed chips into her mouth in handfuls and retrieved pieces of cheese from her burger to inspect before eating them.

He loved how a cheeseburger could become a culinary opera, music supplied courtesy of two straws and a thickshake. He’d always encouraged her noisy eating to annoy Louise and now he simply encouraged it — it was what they did. Anyone watching would have seen an adoring dad and his daughter, doing what dads and daughters did. Frankie slurped shamelessly on the almost empty shake and giggled. Adam swiped one of her chips, swallowed a large and stodgy piece of burger bun and burped loudly to compete. A young couple in another booth, eating quietly and ignoring one another, looked up and across at them with scorn.

Chapter Two

He pulled up outside the factory at the same time as Martin cycled in. Martin stopped and fiddled with the straps on his safety helmet, ignoring Adam and blocking access to the park closest to the office entrance. At least once a week there was a silent tussle over the car park. This morning’s challenge was head-on. Adam could idle the engine and wait until Martin had unstrapped his helmet and moved his cycle, or simply move to a park further along. Martin looked up from under his helmet just as Adam decided to park elsewhere. It wasn’t the triumph he saw that irked him; it was Martin’s casual unconcern — a stark contrast to his own preoccupation with parking hierarchy.

Adam remembered the news item about the man whose mouth wouldn’t shut and his own mouth opened again at the thought. Poor bastard. He imagined the doctors forcing the man’s mouth shut. Had they pushed the jaw up from the bottom and had the man’s teeth cracked on impact? Perhaps a nurse with cool but soft hands had massaged the man’s throat until it relaxed. Adam felt saliva in his mouth, swallowed; his jaw slackened and he greeted Martin with a warm grin. Martin grinned back, thinking it was for him. And in a way it turned out it was. Because you couldn’t take back a smile and say, ‘That’s not yours!’ In they walked, over the threshold of industry, into the dusty reception (he’d have to talk to the cleaning contractors), not quite arm in arm but, as far as the receptionist could tell, management in unison.

‘Good morning.’

The receptionist was speaking into the phone and to Adam and Martin, indicating by the tilt of her head and a finger pointed at her headphones that they were not the only people she was addressing.

‘Adam, I mean Mr Hayward is the man you want … oh, I see, you want the production manager … yes, yes, it is Martin.’

And now she was looking at both Adam and Martin wanting confirmation that one of them would rescue her and who would it be? And obviously the person at the other end of the phone wanted Martin, not Adam. Another little triumph!

‘I’ll take it Paris, just put it through.’

Martin remained neutral; he took his triumphs seriously but he never took advantage. It was enough that Paris was a witness, without gloating.

In three easy strides, he had climbed the six stairs to the production office and disappeared. Paris took off her headset and waved a courier pack at Adam, mouthing the word urgent. It was as if she thought she was still on the phone. Adam reached over and took the red and silver package, which was soft and squishy rather than flat and official.

‘Thank you, Paris.’

Paris was new to reception. She was plump, plain and most unlike Adam’s idea of Paris. But mothers weren’t to know when they beamed down at their newborns just how they would unfold. A newborn Paris might have held all the promise of Europe’s most fashionable city when she opened her eyes. Maybe her nose had hinted at something.

An urgent courier bag. Back when Adam believed in urgency he would have acted immediately, eagerly. But he’d learned that even in manufacturing when deadlines meant the difference between profit and loss, urgent could be downgraded by a simple act of will. A deadline missed was often an opportunity in disguise. (God, the worst thing now was to hear himself spouting Martin’s rhetoric. Martin trotted out theories like newspaper headlines. Relevant and up to date until tomorrow. Adam’s own wisdom, as he saw it, was an accumulation of experience — one in particular — and the ability to reinvent himself in the light of it. What he loathed in Martin was his ability to reinvent at such short notice and with sometimes appalling accuracy.)

He felt the courier pack. Whatever was inside took up only about a third of the A4 package. It was the irregular, soft shape that interested him, not the urgent sticker. He walked up the stairs, one at a time, carefully, in contrast to Martin’s energetic two at a time. The production office was adjacent to his own cubby-hole — almost a broom cupboard actually but he loved his own space, a hangover from the heady eighties when management ruled and required an office.

Martin had created an open-plan environment and if Adam wanted privacy, he had his broom cupboard. It was where he could smoke. Of course the production office was entirely smoke free … the bureaucrats had seen to that. Technically speaking, instead of hiding in his broom cupboard, Adam ought to smoke outside, huddled in the wind, a narcotics addict visible to passing traffic, available for scorn. He’d told Louise he’d given up, but every third or fourth morning he scrabbled through his top drawer (parking tickets, boxes of staples, postage stamps, old credit cards and endless receipts) and found the box of matches hidden at the back. His cigarettes were easier: the inside top pocket of his raincoat, which hung on the back of his door and which he never wore — a good place to house ciggies … especially if Louise poked around in the office. Actually, he hid them from himself as well, as with the door open (open-door policy as instigated by Martin) the raincoat was hidden, temporarily averting temptation.

Adam opened the only window in his broom cupboard that would open. The others had refused to budge after the last paint job. His view was of the eastern hills. Bush, scrub and the suburbs. People put up with the wind so they could sit on top of the hill and gaze across the industrial wasteland to the harbour — that was his take on it. But Martin, who was newly married and owned a ‘lifestyle’ property somewhere on the hill, described it as a panorama. Well, if you liked shopping malls and factory chimneys …

Adam looked up as Heather approached — heavy chest, heavy breathing and heavy tread … all the attributes of a secretary suited to manufacturing. An ‘unclaimed treasure’, she called herself. Thwarted in love and yet lo

veable for that very reason: that was how Adam regarded her when she brewed his morning cup of tea at just the right time, tone and temperature. (Not insipid and milky, yet not the colour of Ayers Rock.)

‘They’re waiting for you.’

Heather tilted her head in a backwards–sideways manner to indicate Martin’s production team just across the corridor. She shared Adam’s opinion of Martin when she was with Adam, but he could never be quite certain it wasn’t the other way around when she talked with Martin. Blind loyalty from secretaries was now both unfashionable and unlikely. Loyalty defied definition as a competence, unlike initiative, enthusiasm and word processing. Heather weighed in well on initiative, was overweight on enthusiasm and probably, if he was being picky, not quite full weight when it came to word processing. Which was why his bill for contract staff (mainly WP support) was rising every day. Martin wanted reports. Heather agreed, except she needed help to produce them.

Heather caught sight of the courier pack. She lifted it from Adam’s desk, turned it over, squeezed it and then tossed it back. Just as well it was only urgent and not fragile, thought Adam.

As their eyes met across the desk, any curiosity Heather may have felt was disguised. She knew Adam well enough not to pry. In the past, prying had created conflict. Heather hated conflict. She preferred to be ‘on-side’, which was probably why her loyalty remained unmeasurable.

‘Just going to feed Zeus.’

Heather pulled a small packet of pellets from her pocket and waved them at Adam as she retreated.

She kept a chinchilla — a small nervous grey animal that had been born during a storm — in a cage beside the cafeteria, feeding it hay and pieces of apple and those odd little pellets. Heather and Adam had negotiated this at the time of employment and he’d been happy with the compromise: $40,000 per annum plus a cage, instead of the $45,000 the agency had told him he would have to pay. Plus, he had secretly been quite hopeful about a secretary with the imagination to call a chinchilla Zeus. Heather took the creature home with her at night in a small cardboard box. At home it had a free run of her flat. It mostly slept during the day and Adam sometimes wondered what Heather and her chinchilla did in the evenings.

Turbulence

Turbulence